The Everett Commission 1920-1922

Robert W. Venables

July 10, 2020

The Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision favors Native American rights in eastern Oklahoma in McGirt v. Oklahoma, July 9, 2020. Given this decision, it may be reasonable to revisit the Everett Report as applicable to Haudenosaunee sovereignty. The caveat is not to trust white law, period. But the conclusion of the 1922 Everett Report was that the lands west of Rome and those Haudenosaunee lands in the Adirondacks are still within Haudenosaunee jurisdiction. This may be viewed as similar to the Supreme Court’s ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma that the eastern Oklahoma is all on Indian reservations. Although I disagree that the U.S. has sovereignty despite the treaties with the Indian nations of eastern Oklahoma and the Haudenosaunee, the case may lead to some interesting first steps regarding a U.S. recognition of the sovereignty of Haudenosaunee and all Indian nations. The following is a summary of a chapter I am writing on Haudenosaunee sovereignty.

Excerpts from my chapter are as follows.

The Everett Commission’s report is 420 typewritten pages, dominated by transcripts from Haudenosaunee testimonies on national territories within what is today known the State of New York and at Six Nations in what is today known as Ontario. At the end of the committee’s exhaustive work listening to the Haudenosaunee and gathering documentary evidence, Assemblyman Edward Everett, an upstate Republican and the chairman of the Commission, addressed a final gathering of thirty-one Haudenosaunee plus white observers in the “Assembly Parlor” of the New York State Capital Building, on February 24, 1922. Everett gave the group a preview of the conclusion he intended to present to the New York State Legislature:

As chairman of the Indian Commission of the State of New York, I shall find that the Indians of the State of New York are entitled to all of the territory ceded to them by the treaty [of 1768 at Fort Stanwix] made with the Colonial Government prior to the Revolutionary war, relative to the territory that should be ceded to the Indians for their loyalty to said colonies and by the treaty of 1784 [also at Fort Stanwix] by which said promise by the colonists was consummated by the new Republic known as the United States of America and in a speech by General Washington to the conference of Indians comprising the Six Nations and recognizing the Indians as a Nation.[1]

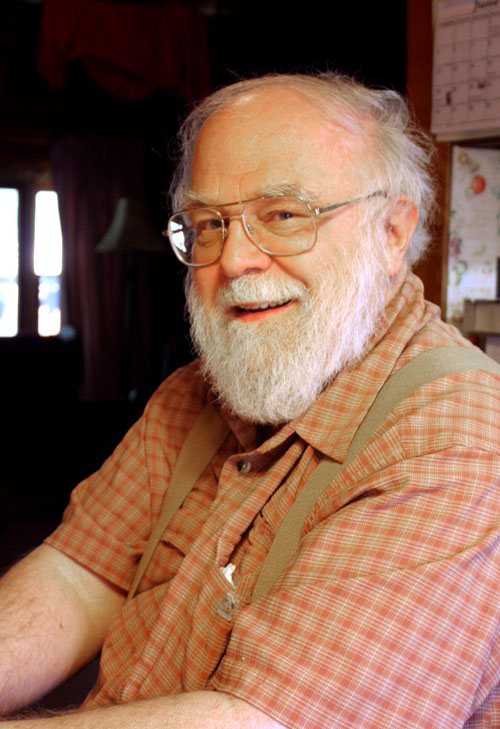

Chief Jesse Lyons speaks at the Albany session of the Everett Commission, February 25, 1922

One of those in attendance at the Albany sessions was the Onondaga leader Chief Jesse Lyons. Lyons rose to speak and used humor to introduce himself by referring to the whites’ frequent confusions over how to refer to Indian people – as bands, tribes, or nations. Each term is a reference to the white belief that all the people of the world follow a socio-political evolution. This is similar to the biological evolution of Charles Darwin: that human societies progress from bands, to tribes, to chiefdoms, and finally to the status of nations or states.[2] On the other hand, the Haudenosaunee were and remain confident that their entire lives, including their socio-political structures, are exactly what the Creator had intended for them. Thus, given Chief Lyons’ worldview, the humor of his opening was even more pronounced:

I am representative from the Onondaga tribe, nation or band whatever may be, they [the Onondagas] say I shall come here and attend this meeting so I am here and very glad I came.[3]

Lyons continued, using the term “George Washington” as a metaphor for the United States:

I am not going to say much, I am going to say a few words of my own opinion, the opinion what I represent. As a Nation, we are strong; we believe that George Washington on [sic] October 1784, at that time sat down thinking about the Indians, simply comes into his mind that he will draw a treaty and he brought that treaty before the Iroquois of New York State Indians. The Indians considered the matter thoroughly and then decided to answer and they signed it, the individual Chiefs and we believe that is the treaty only stands today. We are strongly in favor of that treaty. On the State matter of treaties [that is, negotiated by the State; the following are in the order Lyons used], 1788, 1795, 1793, and 1817 where the State got the justice to make that after George Washington told the thirteen colonies no more treaties shall be made, after he made the treaty, so we believe. George Washington gave us the guarantee we make our own laws and enjoyment and no person would be disturbed. Where the State got the jurisdiction I don’t know. We are here today to try to find out, to understand, we stand outside. I am speaking for the Nation of the tribe of Onondagas. If any lands was disposed of [in] an honest way, we don’t want to lay hands on them. Where it was disposed on dishonest unjust way, we don’t want more than is just what is coming to us. We do believe where the lands today was never sold, was never paid. I have five maps on hand that can reduce it where the white man take possession today that he has no justice to hold that possession. So, I won’t say much about it today. I have been taking up this matter too long with Mr. Everett, he knows who I am and what I am trying to do. One thing I am very glad, we had it once a white man that was George Washington, and the second white man shows up Mr. Everett, and his stenographer [Lulu Stillman] goes around now without pay trying to do what she can. I thank you very much for the work you all are doing to show the Indians the equal rights on justice. So, I will say,- “Mr. Everett, go as far as you can, find out where our rights are.” We are here today to try to find out the benefits for the Indians and not only for the Indians but the whites. There is a day coming, we will have to get together again and let us with justice not because you get the best of me, because you have most men and money that I have; but justice because we are different color. I don’t blame this young class people just growing up what was done years and years ago. George Washington guaranteed he was going to be our brother and made this constitution of the Thirteen Colonies accept and agree. Every time our Brother gets into trouble, we get up and help him. We believe that he is our Brother. What our people done when you fight against the British [during the War of 1812]? We got up and fight to. What when you had trouble with Germany? How many Indians volunteered to enlist?… What our brother he guaranteed us that is what we stand by today.[4]

A Voice from Akwesasne

Michael Solomon, a Mohawk from Akwesasne (St. Regis) on the St. Lawrence River, noted

According to the latest developments and as it has been ably presented to us people, it appears that these transactions are invalid and as such it is necessary that the Commission should take this into consideration in its final findings upon the status of the New York State Indians for it is necessary that the title be gone into and determined. Speaking of title I may be permitted to read to you a short paragraph bearing on the subject of title, the claim of New York State by virtue of the grants made by the English King to the Duke of York is to my mind not binding in 1922 in an enlightened Court of law.

“Title of lands by an established law recognized by all civilized nations is naturally vested in the primitive occupants and cannot be taken from them unjustly without their consent….”

In view of these paragraphs just read to you, to my mind altho I am not a lawyer, it conveys to me the impression that the Indians unqualifiedly have the true title to these lands, it was their domain, their country from time immemorial, before Columbus discovered this country. It is their true territory irrespective what the King of England says.[5]

Everett then summarized his conclusions. But he did so in a way that reflected his own bias as a lawyer licensed by the State of New York, sincerely believing as he did that in the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix the United States had dominion over all Haudenosaunee lands but ceded some of those land back to the Haudenosaunee – an interpretation that depended upon the Doctrine of Discovery. Lulu Stillman’s margin notes make it clear that she believed that the Haudenosaunee had never given up any of their lands and thus it was impossible for the United States to “cede” some of that land back to the Haudenosaunee. Thus in Stillman’s view, as in the word “reservation,” it was the Haudenosaunee, not the whites, who did the “reserving.”

[Everett:] I therefore, conclude that the territory set apart to the Indians of the State in the treaty of 1784, ceded to them certain parts of this State and provided that they could not dispose of the same without securing the consent of the United States and by first offering the territory that they were vested of to the United States. [At this point in the margin of her copy of the transcript, Stillman wrote “They were not Indians of the State no land was ceded to them as they held allodial title.”]

[Everett:] I contend, as a conclusion of law, that the individuals claiming to own territory ceded to the Indians in 1784, must show that their title comes from an instrument similar to and of equal force as the treaty which ceded the land to the Indians at the above named date; namely 1784. [In the margin, Stillman wrote: “Everett, no land was ceded to Indians”][6]

Everett included this strong affirmation:

I now issue a challenge relying on the decision of the courts of the world in the disposal of this question.[7]

Everett then called for a vote for or against his report and conclusion, and all who were present unanimously voted “Aye.”[8] The meeting was then adjourned.

Everett Report Rejected by Legislature

The Legislature of New York refused to accept the report when it was delivered by Assemblyman Everett. The Federal U.S. Government did nothing and even misfiled their copy. The Haudenosaunee not only kept the intent of the report alive through their oral traditions, they kept copies of the report and a complete report with local notes was slowly pieced together at various Haudenosaunee locations.[9] The State Library in Albany eventually obtained and filed the copy kept by Everett’s secretary and confidant, Lulu Stillman. It is this report that is quoted above.

A 2016 Reminder to the White Settlers

Although the Everett Report has been ignored, the Haudenosaunee remain sovereign. In 2016, Irving Powless, Jr., an Onondaga Haudenosaunee Chief, reminded the settlers:

Although physically situated within the territorial limits of the United States today, Native nations like the Onondaga Nation and the other members of the Haudenosaunee retain their status of sovereign nations.[10]

####

REFERENCES

[1] Everett Report, 324.

[2] “Band, tribe, chiefdom, state” is an interpretative mantra called “processualism” as exemplified by Peter Farb in his Man’s Rise to Civilization as Shown by the Indians of North America from Primeval Times to the Coming of the Industrial State (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1968) and is still used by some “processualist” anthropologists and others.

[3] Everett Report, 372.

[4] Everett Report, 372-374.

[5] Everett Report, 389.

[6] Everett Report, 416.

[7] Everett Report, 417.

[8] Everett Report, 418.

[9] Personal communications with Irving Powless Jr. 1972 to 1978 and personal observations, including carefully examining a photocopy of a copy kept at Akwesasne.

[10] Chief Irving Powless Jr., Who Are These People Anyway? Lesley Forrester, ed. (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2016), 56.