When the Onondaga gather, the Ganoñhanyoñh is recited. This ritual gives thanks to all of the living parts of creation that includes the cool water. Without which there would be no life.

“Water runs through the veins of Mother Earth,” stated Tadodaho Sid Hill. “It is so very important that we give thanks to the waters. Water is so intertwined in our culture. It’s a part of our creation story, our water clans like the turtle, beaver, eel, and even the creation of the Haudenosaunee itself.”

“Water runs through the veins of Mother Earth,” stated Tadodaho Sid Hill. “It is so very important that we give thanks to the waters. Water is so intertwined in our culture. It’s a part of our creation story, our water clans like the turtle, beaver, eel, and even the creation of the Haudenosaunee itself.”

The creation of the Haudenosaunee saw an Onondaga named Hiawatha try to strive for peace. In his quest, Hiawatha’s daughters were killed. Covered in despair, Hiawatha came upon a small lake which revealed to him purple and white shells. It is these shells which Hiawatha created our first wampum strings which the Onondaga still continue to use today. The original, evil Tadodaho used Onondaga Lake to create waves and storms of death to all that wanted peace. It wasn’t until the Peacemaker in his canoe made of white stone was able to calm the waters and straightened the mind of Tadodaho to good along the shores of this sacred lake.

Living now in peace with their brother nations, the Onondaga made their home along Onondaga Lake and Onondaga creek. Homes and villages grew all over the area but the Onondaga relied on the waters of the creek and lake for sustenance.

“Not only were the waters a great source of water for agriculture, but the water fed us,” added Tadodaho. “Our diet consisted of mostly fish. We harvested the fish in the warm months from Onondaga creek and the Lake. The fish were so plentiful, that Chief Irving Powless Sr. told stories of when the creek was so full of fish, he thought that he could walk across the creek on their backs.”

In 2011, sculptor Peter W. Michel was inspired by Chief Powless’ story an erected a sculpture along Onondaga Creek next the Seneca Turnpike to help remind the people of Syracuse that Onondaga Creek has been a lifeblood for the Nation for many generations. Unfortunately, for many decades now, the formerly clear water of Onondaga Creek has been chocked with sediment and has become increasingly salty, polluting most of its former uses and providing no sustenance today to the Onondaga Nation.

In 2011, sculptor Peter W. Michel was inspired by Chief Powless’ story an erected a sculpture along Onondaga Creek next the Seneca Turnpike to help remind the people of Syracuse that Onondaga Creek has been a lifeblood for the Nation for many generations. Unfortunately, for many decades now, the formerly clear water of Onondaga Creek has been chocked with sediment and has become increasingly salty, polluting most of its former uses and providing no sustenance today to the Onondaga Nation.

“This entire watershed was the life blood of the Onondaga,” stated Joseph heath, General Counsel for the Onondaga Nation. “Their history is connected to these waterways, their way of life, and who they are connected to the creek and lake. It is terrible to see the condition that the creek and the lake now are in.”

Onondaga Creek wasn’t always in this in this condition. The environmental firm called The Chazen Companies looked into the history of the watershed and Onondaga Creek through documents generated by the United States Geologic Service (USGS), the USEPA, the NYS Department of Environmental Correction, academic researchers, and others.

“The history of the creek has been meticulously recorded,” said Russell Urban-Mead, Certified Professional Geologist and lead investigator from The Chazen Companies.

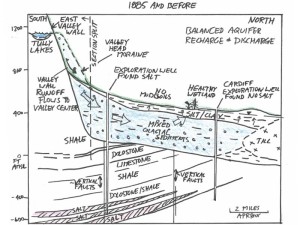

In 1860, Ernest Solvay invented a method to use salt brine and limestone to make soda ash (soda ash is a main ingredient in the making of glass). The salt marshes along the Shore of Onondaga Lake were insufficient for the amount of salt needed for industrial production of soda ash. Therefore the mining of salt brine began south of Syracuse (the Salt City) near the Onondaga Nation lands north of small town called Tully, New York. Salt was found deep below Tully Valley. Before mining began, this salt rock was totally isolated from the Onondaga Valley and Onondaga Creek by overlying shale, limestone, and approximately 400 feet of sediments.

“Even though the rock salt was more than 1,200 feet below the Tully Valley, it seemed a perfect fit for the mining of salt brine,” says Joseph Heath. “Because Tully’s elevation is significantly higher than the City of Syracuse, they drilled wells, diverted fresh water down into these wells to create a return flow of brine and hollowed out logs to transport the brine through LaFayette, Cardiff, and the Onondaga Nation, to the city.

“Even though the rock salt was more than 1,200 feet below the Tully Valley, it seemed a perfect fit for the mining of salt brine,” says Joseph Heath. “Because Tully’s elevation is significantly higher than the City of Syracuse, they drilled wells, diverted fresh water down into these wells to create a return flow of brine and hollowed out logs to transport the brine through LaFayette, Cardiff, and the Onondaga Nation, to the city.

Gravity brought the salt brine to the industrial plants along Onondaga Lake.”

Solvay Process (which became Allied Chemical and later Allied Signal) first used water from the nearby Tully lakes to mine the brine. They would pump fresh water down 1,200 feet into the isolated salt deposits. The fresh water dissolved the salt creating a series of deep, expanding caverns and returned to the surface as salt brine that then was sent to Solvay Process factories, on the shore of Onondaga Lake. Where rock salt was dissolved, caverns expanded and grew at great depth below Tully Valley.

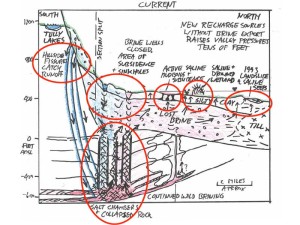

According to the report written by the Chazen Company (“the Chazen Report”), the mine operator monitored the amount of fresh water being pumped into the brining wells. The industry’s own records show that 40-60% of the injected freshwater was never recovered.

As stated in in the Chazen Report, “[t]his means that for every gallon of brine removed to Syracuse, an equivalent volume of brine was lost below ground level, becoming a source of uncontrolled, lost, and pressurized brine.”

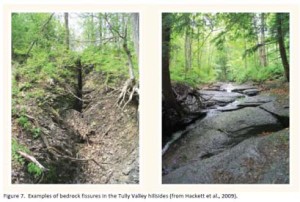

The caverns created by the mining operations expanded outward in an uncontrolled way and had no roof supports, resulting in rock collapses leading all of the way to the surface. The cavities created by the large amount of salt being removed from the valley, also created sinkholes and subsidence in the valley and opened cracks or fissures in the surrounding hillside.

The Chazen Report reviewed the effect of these changes in the geology in the area. Before mining began, rainfall and snowmelt would go down the hill to support Onondaga Creek. Some of this water would go into the hillside rocks and valley sediments as shallow groundwater recharge, but most entered Onondaga Creek directly. During this period, the Onondaga Nation and USEPA reports document that the Creek was clear and sustained a healthy fish habitat.

But the rock collapses, sink holes and hillside fissures created new downward paths for surface water runoff from the surrounding hillsides and fresh groundwater that had previously been isolated from the rock salt. Water that formerly flowed over the land’s surface to the creek or remained in the shallow fresh groundwater was being diverted into the deep rock salt formations. The extra water flowing into the deep rock formation not only generated brine, it also over-pressurized the subsurface aquifer. Eventually, these new paths began supplying enough fresh water to make brine without the need to inject water from the Tully Lakes.

According to the Chazen report, by “1958-1959, Allied Signal . . . realized it could now generate and export brine without formally injecting Tully Lakes freshwater at all; their brine generation practices were now fully supported by uncontrolled surface flows entering subsurface brining chambers through the fractured entry conduits developed during the early mining years.”

Industry continued to draw brine from the area, but increasing subsurface pressure also drove lost salt brine outward and upward. In 1988, Allied stopped removing brine, but did not seal the new subsidence-, sinkhole- and fissure-created pathways. As a result, the Chazen Report notes that brine production has continued with no pressure relief from brine harvesting. During this period, area residents reported salt water intruding into their domestic wells. New springs began discharging water in many places in Tully Valley and scientists recorded sharply increased pressures in groundwater.

The result was the accelerated discharge from increasingly active mudboils. A mudboil is not a common phenomenon in nature. It is quite rare, occurring only where pressurized groundwater penetrates upward through overlying materials with enough velocity to transport sediments along with it. Mudboils are so rare that scientists have been coming to Onondaga Creek to study them for decades, providing ample information over time. The first documented mudboil erupted in Tully Valley in the late 1880s, just years after solution mining began. And since most of this pressured water was passing through the deep salt chambers, the Tully mudboils are particularly unique because over time they came to reflect the brine pressure source and became very salty.

The result was the accelerated discharge from increasingly active mudboils. A mudboil is not a common phenomenon in nature. It is quite rare, occurring only where pressurized groundwater penetrates upward through overlying materials with enough velocity to transport sediments along with it. Mudboils are so rare that scientists have been coming to Onondaga Creek to study them for decades, providing ample information over time. The first documented mudboil erupted in Tully Valley in the late 1880s, just years after solution mining began. And since most of this pressured water was passing through the deep salt chambers, the Tully mudboils are particularly unique because over time they came to reflect the brine pressure source and became very salty.

“A saline mudboil is a mixture of muddy salt water, silt, and clay,” added Joseph Heath. “Every day, mudboils discharge this muddy salty mix into Onondaga Creek to a rate of 20 tons of silt a day!”

Tadodaho explains the effect on the community. “Upstream from the mudboils, the Creek is a great habitat for trout fishing. By the time the water reaches the Nation, we do not fish anymore. The water is so muddy that nothing can live in these waters anymore. We can’t use what we used for centuries. It is a shame.”

The Chazen Report characterizes the mining operations in the Tully Valley as ‘wild brining’. The report defines ‘wild brining’ as the industry term for creation of brine without controls on fresh water used to create brine, the size of subsurface mined areas, or the directions in which mining caverns expand. When mining began, the mine operators knew how much water was being injected into the brine mining field, but made few, if any, efforts to monitor or control the size, location or direction of expansion of the subsurface caverns or to limit the amount of salt removed from any one area. Once lake water was no longer needed for brine production, the amount of water flowing into brining caverns through hillside fissures and collapsed rock zones was unknown and cavern size, location and expansion direction remained uncontrolled and unknown. As before, much of the water entering the brine mining fields continued to escape into the deep rock formation and overlying aquifer, eventually reaching the surface as increasingly salty mudboils.

The Chazen Report characterizes the mining operations in the Tully Valley as ‘wild brining’. The report defines ‘wild brining’ as the industry term for creation of brine without controls on fresh water used to create brine, the size of subsurface mined areas, or the directions in which mining caverns expand. When mining began, the mine operators knew how much water was being injected into the brine mining field, but made few, if any, efforts to monitor or control the size, location or direction of expansion of the subsurface caverns or to limit the amount of salt removed from any one area. Once lake water was no longer needed for brine production, the amount of water flowing into brining caverns through hillside fissures and collapsed rock zones was unknown and cavern size, location and expansion direction remained uncontrolled and unknown. As before, much of the water entering the brine mining fields continued to escape into the deep rock formation and overlying aquifer, eventually reaching the surface as increasingly salty mudboils.

With the unmonitored brining of salt, the cavity grew and grew. It is estimated that where there used to be a layer of salt, there are caverns that could hold 35 Carrier Domes. And every time it rains or the snow melts, surface run-off cascades into subsurface rock formations, generating additional brine and causing caverns to continue to grow. As the Chazen Report notes, ‘wild brining’ is essentially continuing in the Tully Valley.

“The rock fissures are just the tip of the problem,” added Joe Heath. “The salt layer used to help support the hills surrounding the watershed are gone. Now there is just a huge hole. This creates a vacuum, Above these voids in the subsurface, large sink holes and large areas of subsidence, have been documented and these areas are surrounded by hundreds of rock fissures on the hillside.”

“The rock fissures are just the tip of the problem,” added Joe Heath. “The salt layer used to help support the hills surrounding the watershed are gone. Now there is just a huge hole. This creates a vacuum, Above these voids in the subsurface, large sink holes and large areas of subsidence, have been documented and these areas are surrounded by hundreds of rock fissures on the hillside.”

In 1993, the area saw what could happen to the valley. As the salt continues to dissolve away the structure of the hills, the hill can give way to its own weight. South of the Nation in the town of Cardiff, there was an unexpected mudslide. Some investigators have said this was just a natural response to wet weather, but USGS documented swarms of salty springs around the landslide area and continues to record high pressures in the groundwater formation that may have helped lift the wet hillside soils.

“Half of the hill just let loose,” recalled Joe Heath. “Tully Farms Road was buried in 12 feet of mud and people’s homes were wiped away but luckily no one was seriously hurt.”

Tadodaho stated about the mudslide, “It was like Mother Earth was giving us a warning. She was telling as that she is sick. We have to listen because events like this are important reminders of our duty to take care of our Mother Earth.”

There are other warnings as well.

The early mudboils were freshwater and, over time, have become increasingly salty. The Chazen report notes that “[m]uch like a garden hose first discharges water [already] in the hose before delivering refreshed water from the house, rising pressure generated by lost brine first resulted in mudboils that purged fresh aquifer groundwater before the mudboils began discharging salty water.”

The current composition of mudboil discharges matches the deep brine solution salt. As a result of these discharges, Onondaga Creek has become increasingly sedimented and salty. The Creek has and still is undergoing a lot of change.

The current composition of mudboil discharges matches the deep brine solution salt. As a result of these discharges, Onondaga Creek has become increasingly sedimented and salty. The Creek has and still is undergoing a lot of change.

USGS and the current landowner, Honeywell, have tried to remedy the situation. To limit silt loads, pressure relief wells were placed by the mudboils only to clog, be caught in expanding subsidence areas around existing mudboils and sink out of sight, or become the outlet for new mudboils. Large berms were created to try to stop the flow of mud into the creek only to be overrun. A feeder stream was diverted around the mudboils only to have a new mudboil begin in the middle of the Creek. None of these efforts sought to address the increasing salty nature of the mudboils.

“Obviously Allied and the state and federal agencies knew that the Creek needed help or else they would not have tried all of these measures,” stated Heath. “But until we stop the wild brining that is continuing today, these remedies are just Band-Aids to the larger problem. This is not only affecting the stream, but it’s also dumping all of this silt into the Lake.”

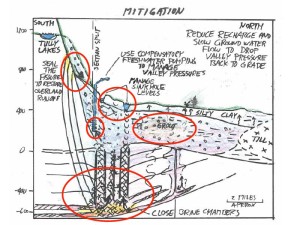

After studying the data, The Chazen Companies has some ideas of how to help the Creek. The report recommends sealing off the fissures in the hillside, to greatly reduce the freshwater entering the mines and slow the rate that the salt is dissolving underneath the valley. Chazen also recommends the monitoring and continued diversion of freshwater around the existing sink holes and consideration of extracting fresh groundwater near the former mining area to lower groundwater pressures and intercepting water that is otherwise ending up as brine, as well.

Heath explains details from the Chazen Report. “There are voids and caverns at depth that continue expanding as long as freshwater continues to seep down and become brine. Sealing, isolating, and filling these caverns would go a long way to the stabilization of the valley as well as the cessation of wild brining.”

“As Mother Earth has already shown to us,” said Tadodaho. “She needs our help to heal herself. If we are able make her healthy again, we can be healthy too.”

A healthy stream would go a long way towards that.

Read the entire Saline-Tully-Valley-Mudboils report.

Watch the video: The Tully Mudboils