Syracuse.com

By John O’Brien and Mark Weiner

The Onondaga chiefs brought the news to their people in a meeting at the Longhouse Thursday night.

The next day, the tribe would finally file a claim in federal court to ownership of more than 2 million acres of land in Upstate New York, after generations of talking about it.

A 17-year-old boy stood up. He asked the chiefs for advice.

“I’m afraid to go to school tomorrow,” the boy said, according to Onondaga Faithkeeper Oren Lyons. “I know they’re going to ask me, ‘Are you taking my land?’ I don’t know what to tell them.”

It’s one of the questions the chiefs prepared for, especially after the hostile reactions to land claims from other nations of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy.

“When they ask, tell them this is a filing of a very old grievance, over 200 years old, that it’s taking place at the insistence of the state of New York, and that there will be no evictions, and that we’re seeking a safer environment,” the chiefs told the boy. “If you can get that much out, you’ll be doing fine.”

The Onondagas took the same approach leading up to Friday’s filing. They met with leaders of the city and county, of Syracuse University, and legislative leaders in Albany and Washington, D.C., to warn them.

Those political leaders reacted Friday by praising the as good neighbors who plan to use their land claim to prod the state to clean up the environment..

But it immediately became clear that the public officials and the chiefs are at odds over one of the central missions of the land claim. The Onondagas think the state’s planned $451 million cleanup of toxic waste in Onondaga Lake is inadequate and must be upgraded. But officials involved in the cleanup said the plan must move forward without delay.

U.S. Rep. James Walsh, R-Onondaga, said he does not want to see anything disrupt the state’s plan. A spokesman for Onondaga County Executive Nicholas Pirro said the county has similar concerns.

“We’ve made great progress on the lake,” said Pirro spokesman Martin Farrell. “We don’t see any value at this point in stopping or slowing down that progress.”

The state must pick a cleanup plan by April 1. Work would begin immediately and could be done in seven years.

Joseph Heath, the lawyer for the Onondagas, said the nation wants to be treated as an equal partner with the state when it comes to making decisions about the cleanup.

“We’re not advocating slowing the cleanup down,” Heath said. “We’re advocating doing it right.”

Heath said the Onondagas were disappointed to learn about the state’s cleanup plan only days before it was released to the public in November. He said the nation’s leaders wanted to be active partners in choosing a remedy.

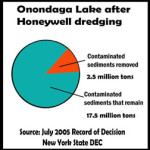

The Onondagas want more extensive dredging of the lake’s contaminated sediments than what’s proposed by either the state Department of Environmental Conservation or Honeywell International, the company responsible for most of the pollution.

Under the state’s cleanup plan, Honeywell would have to dredge 2.65 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment from the lake. The state also wants to cover 425 acres of less-contaminated lake bottom with a cap of sand, gravel and other material.

Honeywell’s $237 million cleanup plan proposed dredging and capping about half of what the state recommended.

Heath said the Onondaga leaders want the lake safe for swimming, fishing and even drinking.

“They want the lake back in the condition that it was taken from them, in the pre-pollution condition,” he said.

Honeywell officials expressed regret that the company was named in the lawsuit, but promised to work with the Onondagas in the cleanup.

The Onondaga leaders made their focus on the environment clear at a news conference announcing the land claim. The Onondagas said they hope to make their claim – which they refer to as a land rights action – as non-adversarial as possible.

“The nation is seeking to work with its neighbors for a healing,” Heath said. In his 30 years as a lawyer, he said he’s never written a lawsuit in the kind of language that the Onondagas’ starts with. It calls them stewards of the land, and describes the lawsuit’s intention of protecting the environment for future generations.

But the Onondagas and the state are already in disagreement when it comes to Onondaga Lake.

“Seeing what’s been going on with the lake cleanup – we’re not satisfied with that,” said Sid Hill, the Onondagas’ tadodaho, or spiritual leader. “We want to be able to drink the water . . . At this time she needs quite a bit of help to get that poison out of her system.”

Heath said he met with state and federal environmental officials this week about the lake.

“It’s not a cleanup plan to us,” he said. “It’s a cover-up plan. It’s nowhere near good enough. You can’t move mercury around and put a cap on it and pretend it’s not a problem.”

The lawsuit filed Friday in federal court in Syracuse names the state, Onondaga County, Syracuse and four businesses that the nation blames for pollution. It accuses New York of violating federal law when the state acquired 4,000 square miles of land from the Onondagas from 1788 to 1822.

Todd Alhart, a spokesman for Pataki, said in response to news of the land claim that the state would “take whatever steps that may be necessary to protect the interests of property owners and taxpayers in Central and Northern New York and the Southern Tier.”

He cited the state’s efforts to clean up the pollution in Onondaga Lake.

“No governor has done more to restore Onondaga Lake and realize its full potential as an important environmental and economic resource for the Central New York region than Governor Pataki,” he said. “The cleanup and revitalization of Onondaga Lake continues to be one of the state’s highest priorities.”

The lawsuit asks a judge to declare the Onondagas as the rightful owners of their aboriginal land – a 250-mile-long, 40-mile-wide band that’s centered in Syracuse.

The suit was filed as other nations in the Haudenosaunee are negotiating with the state to settle their claims.

Richard Tallcot, chairman of the Cayuga-Seneca Chapter of Upstate Citizens for Equality, said it remains to be seen whether a new chapter of his group forms in opposition to the Onondaga claim. It depends on how residents in that area feel, he said.

The Onondagas have talked for years about filing the lawsuit. Five years ago, they were about to file but didn’t after the Cayugas said it might hurt their case that was before a federal jury, Heath said.

It wasn’t until last spring that the Onondaga chiefs agreed that they should file, Lyons said.

Audrey Shenandoah, a 78-year-old clan mother, remembers as a child hearing her grandparents talk about filing a land claim.

“In some ways, it feels like a culmination of all these generations of people,” she said. “I have seen tears for the elders . . . Some of them would say, ‘I wonder if this will ever happen?’ ”

Sue Parsons, a 35-year-old Onondaga, was at LaFayette High School Friday to help handle questions about the land claim.

“I’m very emotional,” Parsons said over lunch at Firekeepers Diner. She was among the Onondagas who attended the news conference. “I felt like I could’ve taken a great big breath with everyone in that room. I was thinking, ‘Holy smokes! This is finally happening and we’re part of it.’ ”

Staff writer Scott Rapp contributed to this report.