Syracuse.com

By Mike McAndrew Staff writer

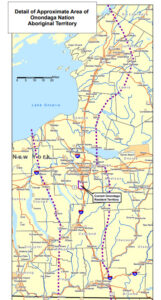

The Onondaga Nation will claim ownership of a 40-mile-wide swath of land stretching from the Thousand Islands to Pennsylvania in a historic lawsuit it will file today against New York, Onondaga County and Syracuse.

The Onondagas will ask a federal court to declare that New York illegally acquired the land in five treaties between 1788 and 1822, and they will ask for title to that land.

The disputed territory includes roughly 4,000 square miles – including nearly all of Syracuse, plus Oswego, Fulton, Watertown, Cortland and Binghamton. About 875,000 people live in the claim area.

Syracuse is the biggest U.S. city to be included in a Native American land claim, according to attorneys and historians familiar with such cases.

While the lawsuit asks a judge to declare the entire area as Onondaga property, Chief Sid Hill stressed the nation will not sue individual property owners or evict anyone from their homes.

The Onondagas – a nation of 1,500 members who live on about 11 square miles just south of Syracuse – are not seeking monetary damages in this action.

The suit asks the court to declare that New York violated federal and state laws when it bought the Onondaga land, said Joseph Heath, the Onondagas’ attorney.

Hill said the Onondagas hope such a ruling would force New York officials to bargain with them on compensation for the illegal sales and to compel New York to better clean up environmental hazards in the claim area – especially Onondaga Lake.

If those state negotiations fail, the Onondagas could return to court to ask a judge for damages.

“With land claims elsewhere, we’ve seen all the negative things that can come out of that. We want to be good neighbors,” said Hill, the tadodaho, or spiritual leader, of the Onondagas.

“We aren’t saying we’re coming after Syracuse because it’s ours. What are we going to do with Syracuse?” Chief Jake Edwards said. “We want to be at the table and help the people in Syracuse make it a healthier place to live.”

Elsewhere in New York, land claims have not hurt anyone’s ability to buy and sell real estate, according to real estate professionals in those areas.

Elsewhere in New York, land claims have not hurt anyone’s ability to buy and sell real estate, according to real estate professionals in those areas.

“Day-to-day, no one will see any difference,” Heath said. “Certainly not until there’s a judgment. Then the state has to figure out how we are going to resolve that.”

John Dossett, general counsel for the National Congress of American Indians, said, “Often there are a lot of concerns about land claims. The immediate concern is: Is the tribe going to take all this land? Experience bears out that’s not what happens. Eviction is not ever seriously considered as a remedy by the courts or the tribes. Everybody understands that’s not on the table.”

Eventually, if the court declares the Onondaga Nation is the rightful owner of the land, the Onondagas hope to:

¨ Force New York to clean up Onondaga Lake and other environmental problems.

¨ Enlarge their untaxed territory by buying land from willing sellers. Hill declined to estimate how much land the Onondagas want or identify any parcels.

¨ Require New York to make payments to the Onondagas for use of their land.

¨

If New York makes a fair offer to settle the suit, the Onondagas will not expect individual property owners to pay any “rent,” Heath said.

The Onondagas – whose leaders oppose casino gambling – say they do not want a casino.

Casinos have been a major part of Gov. George Pataki’s formula to try to settle other pending land claims.

On Feb. 3, Pataki proposed a law to allow the Cayuga, Oneida, Mohawk and Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican nations to open five casinos in the Catskills as part of settlements of their land claims.

The Onondagas’ opposition to casinos “takes away one of the things that’s been used to settle these claims,” said Michael Oberg, an associate professor of history at State University College at Geneseo who researched the Oneida claim for the U.S. Justice Department.

“The Onondaga will take a much different approach in the land/money settlement formula,” said Robert Odawi Porter, director of Syracuse University’s Center for Indigenous Law, Governance & Citizenship. He said the Onondagas are the most traditional of the six nations of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy, and they revere the land.

The Onondagas will be “tough negotiators for strengthening their land base – their unpolluted land base,” Porter said.

Environmental defendants

Instead of casinos, the Onondagas want air and water cleanup to be part of any settlement, Hill said.

Hill said that’s why the Onondagas named as defendants in the suit five Syracuse-area corporations that they allege are polluters:

Honeywell International, which in 1999 merged with Allied Signal Corp., the company that dumped about 165,000 pounds of mercury into Onondaga Lake from 1946 until 1970. Honeywell has proposed a $237 million cleanup of the lake. The Onondagas have said the cleanup plan is inadequate.

The Onondagas consider Onondaga Lake as sacred ground because the Iroquois Confederacy was founded on the lake’s shores hundreds of years ago.

“That’s our cathedral, right there,” Hill said.

Clark Concrete and its affiliate, Valley Realty Development. Clark began operating a gravel mine in Tully in 1997 on land the Onondaga say is sacred. That’s where the Onondagas say wampum, the beads used to communicate and record history, was invented.

Trigen-Syracuse Energy Corp., whose coal-burning power plant in Solvay is the largest air polluter in Onondaga County. Trigen produced 547,270 pounds of pollution in 2002, most of which was hydrochloric acid gas released into the air, according to federal records.

Hanson Aggregate, which has been mining limestone at a 2,280-acre quarry on Jamesville Road in the town of DeWitt since 1996.

Heath said the Onondagas decided to sue Hanson Aggregate about five years ago after he and Hill took a helicopter ride to get photos. From the air, they saw how large the open pit quarry was and were shocked that little had been done to repair the mined land.

“We want to use this action to put us at the table and enforce your laws and exert our laws of responsibility for the earth, water, air and animals,” Hill said.

None of the other Indian nations in New York has made environmental cleanup the cornerstone of its settlement talks, according to attorneys familiar with the claims.

“We’re trying to do a different land-rights action here,” Hill said. “Our concern is the environment and how we as two peoples can live in the area that was our ancestors.”

Long road to today

The Onondagas have been talking about filing a land claim against New York for more than 80 years.

In the 1920s, Laura Cornelius Kellogg, an Oneida from Wisconsin, met chiefs from the six Haudenosaunee nations at the Onondaga Nation many times to try to organize a claim.

Federal civil rules barred Native American nations from filing suits in federal court until 1966, according to SU’s Porter.

Before then, many legal scholars believed Native American nations had to get the United States to file suits on their behalf, said Arlinda Locklear, the attorney for the Oneida of Wisconsin.

In 1997, three Onondagas filed their own land claim against New York and dozens of other corporate defendants. The Onondaga chiefs denounced the effort. Eventually, the suit was withdrawn.

In 1998, Onondaga leaders met with Pataki and told him the nation was close to filing a suit. At the time, the Onondagas were planning to sue for the 108-square-mile territory surrounding Syracuse that they possessed in 1790.

Onondaga Faithkeeper Oren Lyons said the Onondaga system of government requires the chiefs to be in unanimous agreement to take action. Until last year, some of the chiefs did not want to sue.

When they reached a consensus, the chiefs also decided to seek title to all of the land in New York that the Onondagas once occupied.

The Onondagas do not know the precise borders of that aboriginal territory, which stretched from Pennsylvania to the Thousand Islands. They haven’t calculated the square miles or acreage of the area that they are suing over.

“Our territory was between the Cayugas and the Oneidas,” Hill said. “There were no lines in the forest.”

Strongest claim

The Onondagas are the last of the five original Haudenosaunee nations – which include the Mohawks, Oneidas, Cayugas and Senecas – to file a land claim.

Based on the Oneida and Cayuga cases, the Onondagas appear to have a good chance of winning a land claim for any land New York acquired after 1790, said Porter and Oberg.

Those cases relied on the 1790 federal Trade and Non-Intercourse Act, which barred states from obtaining Indian land without Congress’ approval. In the United States’ infancy, New York regularly ignored the Trade Act as the state spread west.

In 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that New York violated federal law by acquiring the Oneidas’ land after 1790 without congressional approval.

In the only land claim suit to go to trial, the Cayuga Indian Nation of New York and the Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma won on the same point and received a $247.9 million judgment against the state in 2001.

Most of the area the Onondagas are seeking in their lawsuit was sold before 1790, and the claim for that land faces a more uncertain future in the court.

That still leaves more than 100 square miles – including nearly all of Syracuse – that New York bought from the Onondagas in four treaties after 1790. None was approved by Congress, according to Heath.

“The Onondagas’ claim on the post-1790 land transactions are as strong as any of the claims that have gone forward,” Oberg said. “It’s as strong as the Oneidas’ claim in the test case.”

Attorney John Campanie – who is defending Madison County against the Oneidas’ pending land claim over 256,000 acres – said the state and counties are much better prepared to fight land claims than they were when the Supreme Court ruled on the Oneida case.

“I’m not going to say it’s a slam dunk one way or the other. The defense in the 1970s was almost nonexistent. There are good defenses now,” Campanie said. “But the state and counties will be burdened by some earlier Supreme Court decisions.”

A tougher test

The Onondagas will face higher hurdles to reclaim title to the larger area – for thousands of square miles in Oswego, Cayuga, Cortland, Tompkins, Jefferson, Tioga and Broome counties. That represents almost one-tenth of all New York.

New York acquired this land – about 90 percent of the Onondagas’ aboriginal territory – in a treaty signed in 1788, two years before congressional approval of Indian land transactions was explicitly required.

No Native American nation in New York has won a court decision covering territory acquired before 1790, said Locklear, who argued the 1985 Oneida case before the Supreme Court.

For this land, the Onondagas will use an untested legal argument, Heath said. While the other cases relied on federal law, the Onondagas will contend that New York broke state law when it negotiated the 1788 treaty.

Heath said a 1783 New York law required that the state Legislature ratify, or approve, any taking of Indian land. New York’s Legislature did not ratify the 1788 treaty until 1813, he said.

By 1813, the Trade and Non-Intercourse Act was in effect, so the treaty should be void, the Onondagas contend.

The Onondagas also say the Onondagas who negotiated the treaties 200 years ago did not have the authority to sell land to the state.

How fast will the Onondaga claim get resolved?

The Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes of Maine sued in 1972 for 12.5 million acres in northern Maine. Just eight years later, in 1980, those tribes accepted an $81 million federal settlement – which experts said remains the largest monetary land claim settlement in the country.

But in New York, land claims typically linger for decades in the federal courts.

The Oneida land claim is 35 years old this year