AN INTEGRAL PILLAR OF THE COLONIZATION and FORCED ASSIMILATION POLICIES OF THE UNITED STATES IN VIOLATION OF TREATIES

by Joseph Heath, Esq.

General Counsel of the Onondaga Nation

INTRODUCTION:

The Onondaga Nation and the Haudenosaunee have never accepted the authority of the United States to make Six Nations citizens become citizens of the United States, as claimed in the Citizenship Act of 1924. We hold three treaties with the United States: the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the 1789 Treaty of Fort Harmor and the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua. These treaties clearly recognize the Haudenosaunee as separate and sovereign Nations. Accepting United States citizenship would be treason to their own Nations, a violation of the treaties and a violation of international law, as recognized in the 2007 United Nation Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

This paper will briefly review the history of land theft, removal and forced assimilation by the United States and how the 1924 Citizenship Act is woven into this disgraceful pattern of deceit and destruction. It will examine the true purposes of the Act and its history. Finally, we will review the contemporaneous resistance to the Act by the Onondaga Nation, on behalf of the Confederacy.

For centuries, the European settlers and then the United States, have struggled with what they have called “the Indian problem”. This “problem” was largely defined as: how to take the Indians’ land and how to deal with the Indians still surviving and continuing to populate their own communities. In spite of the European and American efforts to the contrary, the Haudenosaunee have remained in sovereign control of some of their land, and all of their language and culture. They are still here; they are a people, not a problem.

THE COLONIZATION and FORCE ASSIMILATION POLICIES OF THE UNITED STATES:

In 1992, one of the most respected historians on Native Americans generally and the Haudenosaunee specifically, Professor Lawrence M. Hauptman, wrote an article entitled Congress, Plenary Power and the American Indian, 1870 to 1992, in which he said:

According to the reformist mentality of the late nineteenth century, American Indians had to be transformed for their own good. American Indians could no longer endure anymore as separate enclaves in the dominant white world and must learn to cope with the larger society. Reformers believed in bringing “civilization” to the Indians in order to absorb them into American society through a four-pronged formula of forced assimilation. This “Americanization” process included the proselytizing of Christian missionaries on reservations in order to stamp out “paganism”; the exposure of the Indian to the white Americans’ way through compulsory education and boarding schools; the breakup of tribal lands and allotment to individual Indians to instill personal initiative, allegedly required by the free enterprise system; and finally, in return for accepting land-in-severalty, the rewarding of United States citizenship. 1 (Emphasis added.)

Prof. Hauptman then went on to quote from Henry S. Pancoast, one of the founders of the Indian Rights Association: 2 “Nothing [besides United States Citizenship] will so tend to assimilate the Indian and break up his narrow tribal allegiance, as making him feel that he has a distinct right and voice in the white man’s nation.” (Emphasis added,)

LOOKING BACK:

From 1789 to 1871, the United States entered into hundreds of treaties with Indian Nations, and many of these treaties contained language favorable to the Nations and respectful of their sovereignty. However, “[t]he overriding goal of the United States during treaty-making was to obtain Indian lands.” 3

Until the 1820s, Indians and the fledgling United States interacted with wars and/or treaties. The Haudenosaunee were never defeated in war, and so their treaties of 1784,1789 and 1794 are unique, with clear recognition of their sovereignty. The United States Department of Justice, as recently as 2010, filed a brief in the New York Court of Appeals in which they vigorously and correctly argued that the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua is still valid and the Court of Appeals has agreed. 4

Ironically, despite acknowledging that the Haudenosaunee Treaties are still valid, United States law continues to violate the treaties, and now claims to have plenary power to unilaterally decide when it will break treaties. US law claims the right to tax and regulate, to draft Haudenosaunee citizens and to deny the right of travel.

Recently, the federal courts have concocted a new “equity” defense, which only applies to Indians and thereby, have dismissed land rights actions, despite clear and admitted violations of federal law and federal treaties.

The early treaties, including those of the Haudenosaunee, were essential to the fledgling United States, while it was still threatened by England, and while it was losing the Indian Wars in Ohio in the 1790s. However, once these threats lessened, the federal government started down the path to break the treaties in an attempt to limit sovereignty. The Citizenship Act of 1924 was a very important, final step along this path.

The [federal] government based its Indian policy on treaty negotiations in recognition of the strength and military importance of the Indian [Nations], particularly during the Revolutionary War era. As the immediacy of the British threat diminished after the War of 1812, and the United States no longer feared a British-Indian alliance, critics such as Andrew Jackson advocated that treaty-making be abolished. 5

We will now turn our attention to the historical actions by the executive branch federal government which implemented these colonization and forced assimilation policies, while the Supreme Court and Congress took turns at limiting Native sovereignty.

UNITED STATES INDIAN LAW IS FOUNDED ON THE DOCTRINE OF CHRISTIAN DISCOVERY:

Indian title and rights to land were first addressed by the Supreme Court in 1810, in Fletcher v. Peck: (10 US 87): “What is the Indian title? It is a mere occupancy for the purpose of hunting. It is not like our tenures; they have no idea of a title to the soil itself. It is overrun by them, rather than inhabited. It is not a true and legal possession. . . . It is a right not to be transferred, but extinguished.” (10 US at 121.) (Emphasis added.) The Court went on to justify this claim by observing:

The Europeans found the territory in possession of a rude and uncivilized people, consisting of separate and independent nations. They had no idea of property in the soil but a right of occupation. A right not individual but national. This is the right gained by conquest. The Europeans always claimed and exercised the right of conquest over the soil. (Id. at page 122.) (Emphasis added.)

Based on these unenlightened and prejudiced views, the Supreme Court has repeatedly used the doctrine of Christian discovery to claim the right to take Indian peoples’ sovereignty and rights to land.

In 1823, Indian Nation sovereignty was addressed again by the Supreme Court, in Johnson v. McIntosh, 21 US 543, (1823), when the Court clearly articulated that the doctrine of Christian discovery is the foundation of US Indian law.

In Johnson, the dispute over this land was between two groups of land speculators. One group traced their title to purchases, in 1773 and 1775, from the Indigenous Nations themselves, and another group traced their title to a 1813 purchase from the United State government. The ruling favored the later group and stated: “A title to lands, under grants to private individuals, made by Indian tribes or nations, . . . cannot be recognised (Sic.) in the Courts fo the United States.” (Id. at page 562.) Unfortunately, Marshall did not stop there but went on to write that:

The [Indians] were admitted to be the rightful occupants of the soil, with a legal as well as just claim to retain possession of it, and to use it according to their own discretion; but their rights to complete sovereignty, as independent nations, were necessarily diminished, and their power to dispose of the soil at their own will, to whomsoever they pleased, was denied by the original fundamental principle, that discovery gave exclusive title to those who made it.

While the different nations of Europe respected the right of the natives, as occupants, they asserted the ultimate dominion to be in themselves; and claimed and exercised, as a consequence of this ultimate dominion, a power to grant the soil, while yet in possession of the natives. (Id. at pages 573 and 574.) (Emphasis added.)

The US courts have since held that Indigenous Nation sovereignty has been diminished and that “exclusive title” to, and “ultimate dominion” over their lands has been lost to the Christian “discoverers”. The Onondaga Nation has denounced this ruling and the doctrine, and has worked tirelessly to call for its removal from US law.

Marshall then wrote many pages reflecting that all the European “discoverer” nations claimed their “right of dominion” to “acquire and dispose of the soil which remained in the occupation of Indians.” (575.):

Thus has our whole country been granted by the crown while in the occupation of the Indians. These grants purport to convey the soil as well as the right of dominion to the grantees. (579)

. . .

Thus, all the nations of Europe, who have acquired territory on this continent, have asserted in themselves, and have recognized in others, the exclusive right of the discoverer to appropriate the lands occupied by the Indians. Thus, all the nations of Europe, who have acquired territory on this continent, have asserted in themselves, and have recognised in others, the exclusive right of the discoverer to appropriate the lands occupied by the Indians. (584.)

Lest we think that the doctrine is not currently being used by the US courts to take away Indigenous land rights, we only need to look at the recent Supreme Court and 2nd Circuit decisions that have dismissed the Haudenosaunee land rights actions. In March of 2005, the Supreme Court ruled in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, 544 US 197 (2005), that even when Oneida bought its own stolen land back, within the area protected by the Canandaigua Treaty, it could not “rekindle” its jurisdiction over the land and that it must pay the local property taxes. The first footnote in Sherrill, clearly invokes the doctrine of discovery as a basis for its ruling , (Id. 203)

Three months later, the 2nd Circuit used the Sherrill decision as the basis to dismiss the Cayuga Nation land claim 6 and then, in August of 2010, the Circuit also dismissed the Oneida land claim. 7 Ironically, this string of dismissals and further rulings against sovereignty is based upon “equity”. The courts have created an entirely new equity defense, in contravention of the normal rules of equity, and this new defense only applies to Indigenous Nations’ land rights actions.

After the Circuit’s dismissal of the Cayuga and Oneida land claims, the eventual dismissal of the Onondaga Nation’s Land Rights’ Action became inevitable. Initially, the Northern District made a formal decision to dismiss. 8 After the Nation appealed this dismissal to the 2nd Circuit, I was summoned to oral argument there on October 12, 2012–Columbus Day. The irony of this timing was not lost on the Nation’s leaders.

One week later, on October 19, 212, the Circuit dismissed the Onondaga action in a summary, one page decision. 9 This immediate and summary affirmance of the dismissal is a clear indication of how entrenched “the Sherrill doctrine” has become.

REMOVAL:

“As Indian [Nations] increasingly resisted demands to relinquish their lands by treaties of cession, the federal government accelerated a policy of removing Indians to lands in the West in exchange for their territory in the East. Jefferson had first advocated this approach in 1802, but the first exchange treaty was not concluded until after the War of 1812.” 10

After waging his brutal military assaults on the Five Civilized Nations, Andrew Jackson, once President, signed the Removal Act in 1830, which he forced through both houses of Congress. The Removal Act gave legal cover to a policy of ethnic cleansing of the Eastern Indian Nations, which was always backed up with the use and threatened use of military power.

When the Cherokee Nation attempted to use legal efforts to resist removal, the federal courts joined in with the other branches of the federal government to proclaim further reduction of Indian Nation sovereignty. After the state of Georgia passed laws, taking away the Cherokee Nation’s rights within it own territory and aimed at their removal, the Nation asks the federal courts for an injunction against the state. This resulted in the Marshall court’s decision in The Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia, 30 US 1 (1831): and Marshall wrote that the court would not rule on the merits because the Cherokee Nation was not a foreign nation, but rather that “They may, more correctly, perhaps, be denominated domestic dependent nations. . . . Their relationship to the United States resembles that of a ward to its guardian.” 11 (Emphasis added.)

After the Civil War, the appetite of the United States for more Indian land increased and therefore, the constant attack on Indian sovereignty escalated.

THE END OF TREATY MAKING;

In 1871, a compromise was reached between the House of Representatives and the Senate under which treaty making was terminated, but existing treaties were expressly validated. The Appropriations Act of March 3, 1871, contained the following clause:

Provided, That hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty: Provided further, That nothing herein contained shall be construed to invalidate or impair the obligation of any treaty heretofore lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe. 12

Unfortunately, history has shown that only the first aspect of this act (the end of treaty-making) was implemented, as the federal courts then proceeded to issue decisions that have gutted treaties and attempted to diminish sovereignty step-by-step, in clear violation of the United States Constitution. 13

PLENARY POWER;

Professor Hauptman’s introduction to his section on plenary power begins this way:

For well over one hundred years, the United States federal court system has recognized the doctrine of plenary power, namely the right of Congress to unilaterally intervene and legislate over a wide range of Indian affairs, including the territory of Indian nations. A century of abuse of this doctrine by Congress has motivated some American Indians to suggest that federal Indian treaty-making be reinstituted, thus reinstating the original intent of the framers of the United States Constitution. The noted attorney Alvin J. Ziontz has observed that the doctrine of plenary power “in practice means that Congress has the power to do virtually as it pleases with Indian tribes.” Ziontz added: “Short of that, it justifies the imposition of controls over the lives and property of the tribes their members. Plenary power thus subjects Indians to national powers outside ordinary constitutional limits. 14 (Emphasis added.)

Professor Hauptman continued by concluding that: “Plenary power has an interesting history.” 15 This is a rather sanitized way of saying that Congress and the Supreme Court have simply created this claimed power over Indian Nations, out of whole cloth–with no historical or legal basis or precedent. In fact, the powers claimed by Congress are clearly in violation of the US Constitution.

In 1870, in the case entitled The Cherokee Tobacco, 78 US 616 (1870), the Supreme Court ruled that an act of Congress could supersede a prior treaty, setting the precedent for the doctrine of plenary power. This was the first time that the Supreme Court articulated this doctrine and essentially they concocted it out of whole cloth–they simply made it up. This claim, that an act of Congress can over rule a treaty, set the precedent for the claim of plenary power.

The majority opinion in Cherokee Tobacco, makes only fleeting reference to the Constitutional mandate for the supremacy of treaties, while relying heavily on Johnson v. McIntosh. The problem confronting the court was the language of Article VI,16 clause 2 of the Constitution, which reads: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made of which will be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; . . .”. Because treaties, the Constitution and US laws are placed on an equal footing, no direction is provided as to how to resolve any conflict among or between them.

There was no precedent for this claim that laws can trump treaties, so the Supreme Court made reference to two lower federal court decisions, one was The Clinton Bridge, 1 Walworth 155 (Iowa Circuit, 1867), which involved the question of whether a law authorizing a bridge over the Mississippi River violated an earlier treaty with France that guaranteed unimpeded navigation. That court ruled that this was an international question, which had to be resolved in other venues; that the courts could not decide it. Interestingly, when the Supreme Court affirmed this Circuit Court decision, 77 US 454, (1870), it did not even mention the word treaty and was completely silent on this portion of the ruling.

The next step along this slippery slope towards the plenary power doctrine came in 1883, when the Supreme Court decided the case of Ex Parte Crow Dog, 109 US 556 (1883), in which they over turned a murder conviction of an Indian that had been committed on a reservation because the US did not have jurisdiction over Indian crimes on reservations. This caused such an uproar that, in 1885, Congress passed the Seven Major Crimes Act, 23 Stat. 362, extending federal jurisdiction over specific crimes committed on Indian country. According to one author, this act, for the first time, extended federal jurisdiction “Over strictly internal crimes of Indians against Indians, a major blow at the integrity of the Indian tribes and a fundamental readjustment in relations between the Indians and the United States government.”17 The next year, the Supreme Court upheld this law and its grab of jurisdiction over Indian country in the land mark case of US v. Kagama, 118 US 375 (1886). In this decision, the Court openly admitted that such Congressional authority was not authorized in the Constitution, but used the doctrine of Christian discovery as the basis for this decision:

Following the policy of the European governments in the discovery of America, towards the Indians who were found here, the . . . United States since, have recognized in the Indians a possessory right to the soil over which they roamed and hunted and established occasional villages. But they asserted an ultimate title in the land itself, . . . They were, and always have been, regarded as having a semi-independent position when they preserved their tribal relations; not as states, not as nations, not as possessed of the full attributes of sovereignty, . . . (Id. at 381.) Emphasis added.)

. . .

They are spoken of as “wards of the nation;” “pupils;” as local dependent communities. . . . These Indian tribes are the wards of the nation. They are communities dependent on the United States,-dependent largely for their daily food; dependent for their political rights. . . . The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful, now weak and diminished in numbers, is necessary to their protection, as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell. (Id. at 383.and 384)

This case is still recognized as one of the leading precedents for US Indian law, despite its 19th century, racist language and assumptions of racial superiority. Kagama was cited by then Justice Rehnquist, in his majority opinion in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 US 191 (1978), which was the 20th century Court’s most important decision on severely limiting the jurisdiction of Indian Nations. In Oliphant, Rehnquist ruled that Indian Nations do not have criminal jurisdiction over non-Natives, even when they murder or rape citizens of the Nation on Nation territory.

ALLOTMENT: MASSIVE TAKING OF INDIAN LANDS:

The year after Kagama, Congress passed the (Dawes) General Allotment Act of 1887, which was a conscious attempt to break up the Indian land base, to destroy Indigenous culture and to absorb Native peoples into the dominant society. Reservations were carved up into individual lots, with heads of households to receive 160 acres and all “surplus” land up for sale. Even these individual lots were only protected for 25 years. Indians who accepted allotment were to receive United State citizenship and this was the first congressional act to provide US citizenship to Indian, but only at the expense of sacrificing the Indians’ separate, national identity. Between 1887 and 1934, Indian landholding shrank from about 138 million to 52 million acres.

This combination of the claim of plenary power, with the thirst for Indian lands. set the stage for the 1903 decision in Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 US 535 (1903), in which the Court more clearly articulated the claim of plenary power. Under the 1867 Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek, no part of the Kiowa or Comanche Reservations could be ceded without approval of 3/4 of the adult males. However, a three man federal commission arranged for allotment and the opening up of “surplus” reservation lands to non-Indian. Lone Wolf, who was a prominent Kiowa citizen, sued to prevent this land grab because it violated the 1867 treaty. In rejecting Lone Wolf’s challenge the Court distorted history and wrote: “Plenary authority over the tribal relations of the Indians has always been exercised by Congress from the beginning, and the power has always been deemed a political one, not subject to be controlled by the judicial department of the government. . . . When, therefore, treaties were entered into between the United States and a tribe of Indians, it was never doubted that the power to abrogate existed in Congress.” 18

This historical revisionism is but one of a long string of examples of the Court simply making up facts and law as needed to deny justice and jurisdiction to Indigenous Nations.

NEW YORK’S EVERETT REPORT OF 1922:

In 1919, the New York State Assembly established the New York State Indian Commission, to investigate the status of Indian welfare and land rights in the state, and Republican Assemblyman Edward Everett became its chair. After holding hearings on the territories of the Haudenosaunee Nations, the Commission issued its report, which focused on the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix. This treaty was the basis for the Commission’s conclusion that the Haudenosaunee still retained the title to the original six million acres of their aboriginal territory.

Only Everett signed this conclusion which was ignored by the Assembly and the report was kept secret until 1971, and then its release came only from a former secretary to Everett, Lulu Stillman; not from the state. Obviously, when the legislature’s own commission raised such a strong challenge to the state’s illegal takings of Haudenosaunee lands in the 1790s and early 1800s, the state was deeply concerned.

THE CITIZENSHIP ACT OF 1924:

In January of 1924, US Representative Homer P. Snyder ( R) of New York 19 introduced the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which was modified in the Senate in three important aspects before it was approved by both houses and signed by President Calvin Coolidge on June 2, 1924. The original language had called for the Secretary of Interior to be authorized to grant citizenship to those Indians who applied, but this was removed by the Senate and the blanket grant to all Indians not previously made US citizens was included. So, without consultation with Indians, the US Government simply attempted to force citizenship onto them; thus following the pattern of the Europeans’ attitude that they know what is best for the Indians, regardless of what they want.

In January of 1924, US Representative Homer P. Snyder ( R) of New York 19 introduced the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which was modified in the Senate in three important aspects before it was approved by both houses and signed by President Calvin Coolidge on June 2, 1924. The original language had called for the Secretary of Interior to be authorized to grant citizenship to those Indians who applied, but this was removed by the Senate and the blanket grant to all Indians not previously made US citizens was included. So, without consultation with Indians, the US Government simply attempted to force citizenship onto them; thus following the pattern of the Europeans’ attitude that they know what is best for the Indians, regardless of what they want.

The Senate also removed the word “full”, so that the “grant of full citizenship” was watered down to merely the “grant of citizenship.” The importance of this amendment is illustrated by the very brief legislative history that reveals the only floor discussion on the bill was one question from Congressman Garrett, from Tennessee, who asked Snyder if this bill meant that Indians could vote. Snyder assured him and the rest of the chamber that it did not and that this was still controlled by the states, when he answered: “[I]t is not the intention of this law to have any effect upon suffrage qualifications in any State.” 20

The historical records does not contain any explanation for why Mr. Snyder felt that this unsolicited grant of citizenship did not include the guarantee of the right to vote, but his statement does make it clear, along with the removal of the work “full”, that this Indian citizenship was something less than that enjoyed by non-Indians. In fact, it was not until 1948 that the last state removed the prohibition against Indians voting. This was true despite the claim by the federal government, in the 1940 Selective Service Act, to have the right to draft Indians.

The third amendment to the bill before its passage was the addition of the disclaimer: “That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.” This provision has been interpreted as creating a dual citizenship.

Mr. Snyder was well aware that this grant of citizenship was opposed by the Haudenosaunee, as clearly shown by this statement by him on May 19, 1924 in the House of Representatives Committee on Indian Affairs, after the bill has been amended by the Senate:

I will say to this committee that this bill now carries the provision that I have wanted to see in legislation ever since I have been a member of this committee. The New York Indians are very much opposed to this, but I am perfectly willing to take the responsibility if the committee sees fit to agree to this. 21 (Emphasis added.)

Clearly, the Haudenosaunee had communicated their opposition to the grant of US citizenship to Mr. Snyder before the passage of this law, but, as usual their position was ignored.

HAUDENOSAUNEE RESISTANCE TO THE CITIZENSHIP ACT:

The Haudenosaunee promptly and strongly rejected this blatant attempt at forced assimilation, as noted again by Prof. Hauptman:

For certain Indian nations, the Indian Citizenship Act proved to be a major thorn in their side and was openly challenged in the federal courts. The Grand Council of the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy promptly send letters to the President and Congress of the United States respectfully declining United States citizenship, rejecting dual citizenship, and stating that the act was written and passed without their knowledge or consent. 22

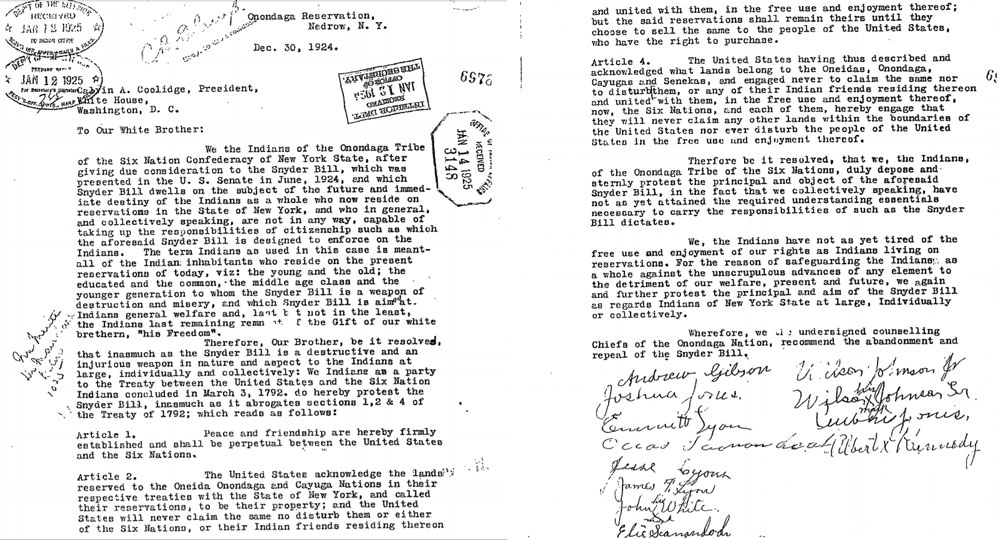

Attached hereto, as Exhibit “A”, is a copy of the December 30, 1924 letter from the Grand Council to President Coolidge, which bears multiple agency stamps documenting that it was received. It reads in part:

Therefore, Our Brother, be it resolved that inasmuch as the Snyder Bill is a destructive and an injurious weapon in nature and aspect to the Indians at large, individually and collectively: We Indians as a party to the Treaty between the United States and the Six Nations in [1794], do hereby protest the Snyder Bill, inasmuch as it abrogates sections 1, 2, & 4 of the Treaty. . . .

Therefore, be it resolved, that we, the Indians of the Onondaga Tribe of the Six Nations, duly depose and sternly protest the principal and object of the aforesaid Snyder Bill, . . .

We, the Indians have not as yet tired of the free use and enjoyment of our rights as Indians living on reservations. For the reason of safeguarding the Indians as a whole against unscrupulous advances of any element to the detriment of our welfare, present and future, we again and further protest the principal and aim of the Snyder Bill, . . .

Wherefore, we the undersigned counselling (sic) Chiefs of the Onondaga Nation, recommend the abandonment and repeal of the Snyder Bill.

The Onondaga Council of Chiefs did not rest with this letter, and the next year, 1925, Onondaga Chief Jesse Lyons was sent to Washington, with wampum belts, to deliver the same message: that the United States needed to be reminded of the treaties they had signed with the Haudenosaunee in the late 1700s, which clearly documented that Onondaga was, and is, a separate, sovereign Nations, and that their citizens are not US citizens.

Attached hereto, as Exhibit “B”, is a copy of a June 7, 1925, New York Times ran an article, which documented this trip by Chief Lyons:

Some priceless wampum belts of the Six Nation of the Iroquois, hidden from white men’s eyes since George Washington saw them at a treaty-making powwow, have been brought out of the “LongHouse” of Iroquois Council Fires on the Onondaga Reservation near Syracuse, N.Y., in an effort to ward off efforts to include the Indians in American citizenship. . . .

It may seem odd that natives lining in the midst of evidence of the opportunities that come with American citizenship should decline–actually fight off–a privilege for which most newcomers clamor.

But the aboriginal Iroquois, after centuries of association with the whites, still maintain a racial reverence for the political institutions fo their forefathers and cling to their treaty rights to detachment and independence. Hundreds of haughty (Sic.) Iroquois, living on ancestral land in Western and Central New York, within a day’s ride from Broadway, believe that to merge themselves in American citizenship would be an unforgivable insult to the Great Spirit of their elders. According to the Indian interpretation, the records woven into the wampum belts preclude them from accepting our citizenship and guarantee their separateness forever. . . .

They laid particular emphasis on the Belt of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, made in 1794, which, according to their reading, gave to “the Six Nations and their Indian friends living with them” the perpetual right to live on their reservations in independent sovereignty, “never to be disturbed.”

This provision the conservative or pioneer Mohawks, Oneidas, Senecas, Cayugas, Onondagas and Tuscaroras, who comprise the Six Nations, construed to mean that they never could be eligible for, not be impressed into American citizenship, no matter how many bills Congress passed, not excluding the bill enacted last fall when citizenship was conferred upon all native Indians in the United States. 23

THE UNITED NATIONS DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES:

On September 13, 2007, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The only countries that voted against its adoption were the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. All four have since at least partially corrected their positions and have supported the Declaration. This Declaration would certainly bar any dominant state from forcing citizenship onto its Indigenous peoples, without any consultation and without their consent, as this is clearly forced assimilation.

The clearest prohibition in the Declaration is found in Article 8 (1): “Indigenous peoples and individuals have the right not to be subjected to forced assimilation or destruction of their culture.” (Emphasis added.) However, the Citizenship Act would also violate Articles 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 of the Declaration.

CONCLUSION:

The Onondaga Nation and the Haudenosaunee have never accepted the authority of the United States to make their Nations’ citizens become citizens of the United States, as claimed in the Citizenship Act of 1924. They rejected this attempt and resisted its implementation immediately after its adoption, because they had the historical and cultural understanding that it was merely the latest federal policy aimed at taking their lands and at forced assimilation.

For over four centuries the Haudenosaunee have maintained their sovereignty, against the onslaught of colonialism and assimilation, and they have continued with their duties as stewards of the natural world. They have resisted removal and allotment; they have preserved their language and culture; they have not accepted the dictates of Christian churches; and they have rejected forced citizenship.

They hold three treaties with the United States: the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the 1789 Treaty of Fort Harmor and the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua. These treaties clearly recognize the Haudenosaunee as separate and sovereign Nations. Accepting United States citizenship would be treason to their own Nations, a violation of the treaties and a violation of international law, as recognized in the 2007 United Nation Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Haudenosaunee call upon the United States to uphold their half of the Treaties and to recognize that they do not have the right to force their citizenship onto an already sovereign people, with whom they made and hold treaties.

Dawnaytoh,

Joe Heath,

Joseph J. Heath, Esq., Onondaga Nation General Counsel

1 Congress, Plenary Power and the American Indian, 1870 to 1992, Lawrence M. Hauptman, Chapter 8 in Exiled in the Land of the Free: Democracy, Indian Nations and the U.S. Constitution. Clear Light Publishers, 1992, page 322.

2 The Indian Rights Association was founded in Philadelphia in 1882, with the initial stated objective of: “bring[ing] about complete civilization of the Indians and their admission to citizenship.” These were non Indians, who might have thought they were doing good, but “by modern standards, had little understanding of the cultural patterns and needs of Native Americans.” (Wikipedia.)

3 Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law, 2005 Ed., p. 29.

4 Cayuga Indian Nation of New York vs. Gould, 14 NY 3d 614 (2010).

5 Cohen, p. 74.

6 413 F. 3d 266 (2nd Cir. 2005.)

7 617 F. 3d 114 (2nd Cir. 2010.)

8 Onondaga Nation v. N.Y., No. 5:05-cv-0314, 2010 WL 3806492, at * 39 (N.D.N.Y. Sept 22, 2010.).

9 Onondaga Nation v. N.Y., 500 F. App’x 87, 90 (2d Cir, 2012).

10 Cohen, p. 45.

11 30 US at 17.

12 Act of Mar. 3, 1871, § 1, 16 Stat. 544 (codified at 25 USC § 71).

13 U.S. Constitution, Art. VI, clause 2 reads: “[A]ll Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; . . .” (Emphasis added.)

14 Hauptman, p. 318.

15 Ibid.

16 It is interesting to note that The Cherokee Tobacco decision incorrectly states that this supremacy clause is in Article IV.

17 Francis P.Prucha, The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians, vol.2 (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1980), p. 83.

18 This ruling and unsupported assumption of plenary power is in clear violation of the Constitution’s mandate that “Treaties are the supreme law of the land.”

19 Synder was from Little Falls, in the Mohawk Valley.

20 65 Cong. Rec. 9303 (1924).

21 Issuance of certificates of citizenship to Indians: Hearing on H.R. 6355 Before the Committee on Indian Affairs, 68th Cong. 1, at 13-14 (1924).

22 Ibid. p. 324. The Haudenosaunee did not file court actions, but exercised the process established in Article Vii of the 1794 Canandaigua Treaty, which provides that disputes between the United States and the Haudenosaunee will be handle with direct communications between the President, or his designee, and the Councils of Chiers.

23 The racist and culturally arrogant language and attitude of this article, from one of our more “progressive” newspapers, illustrates the racism and prejudice which Indian face every day in the US. Better journalism and research would have documented that the language of the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua clearly reads exactly as stated by the Haudenosaunee.