Syracuse.com

Mark Weiner

A decade after the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the Onondaga Nation’s historic claim to its ancestral lands, an international panel representing 35 countries will conduct its own review of the case.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights agreed to hear the Onondaga Nation’s claim that the United States and New York state unjustly took its land more than 200 years ago.

The commission is part of the Organization of American States, a group of Western Hemisphere nations that promotes democracy, human rights, security, and development.

The commission is part of the Organization of American States, a group of Western Hemisphere nations that promotes democracy, human rights, security, and development.

Any decision from the Washington, D.C.-based commission would not be legally binding and is unlikely to be recognized by U.S. officials.

The Onondaga Nation filed its claim with the commission in April 2014, six months after the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an appeal in its land claim case. Nine years later, the commission decided in May to accept the case.

The nation initially filed its first lawsuit in 2005, claiming New York illegally obtained about 4,000 square miles of land in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The roughly 2.5 million acres now includes nearly all of Syracuse, Oswego, Fulton, Watertown, Cortland and Binghamton.

The Onondaga Nation said the taking of its land is an injustice of which all Americans should be ashamed.

The nation has argued that the loss of its land violated the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua that guaranteed the Six Nations of the Iroquois “the free use and enjoyment” of their land.

Heath said the case before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights is a final attempt for recognition of its rights.

“The allegation is that it was a human rights violation to allow land to be taken illegally, it’s a human rights violation to allow the land to be trashed the way it has been, and it’s a human rights violation not to allow the court systems to have a remedy for treaty violations,” Heath said.

The U.S. Department of State filed a response with the commission in August 2022 asking for the claims to be ruled inadmissible.

The State Department said that U.S. courts had already assessed the claims “at great length in multiple lawsuits and have concluded that petitioners are not entitled to relief as either a matter of law or equity.”

Heath said the Onondaga Nation is not seeking financial compensation, nor does it want to force people from their homes or take land from people involuntarily.

Instead, nation leaders hope the case can lead to negotiations that would lead to the return of ancestral lands now in control of New York state, Heath said.

About 1,000 heavily forested acres in Tully were returned to the Onondaga Nation last year in an agreement brokered by federal and state officials with the landowner, Honeywell International. Honeywell inherited the land through a merger with Allied Chemical.

It was one of the largest land transfers made to an Indian nation in the United States, and the first time that land had been returned directly to a New York nation, government officials said at the time of the deal.

State officials said the land transfer was an attempt to right the wrongs of the past.

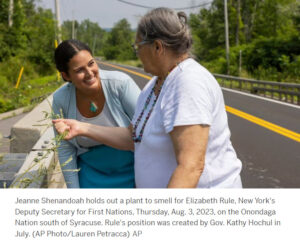

Heath said New York state, under Gov. Kathy Hochul, has made historic inroads with the Onondaga Nation.

In August, Hochul became the first New York governor to visit the Onondaga Nation in at least a half century. The land rights case was not among the issues discussed at that meeting, he said.

But Onondaga Nation leaders are hopeful that a favorable decision from the international commission will convince state and federal officials that it’s time to acknowledge the wrongs of some 240 years ago, Heath said.

“Ultimately, we can’t just sit back and accept the decision from the U.S. courts that there is no remedy whatsoever,” Heath said. “The Onondagas aren’t going to just give up. We have to keep at it. We hope that people remember that the land was taken illegally.”