Syracuse.com

By Steve Featherstone

Tucked in a corner of a city park in Syracuse’s Valley neighborhood, sandwiched between two CNY thoroughfares, one ancient—Onondaga Creek—and one modern—West Seneca Turnpike—is a metal sculpture called “Honoring the Onondaga Creek.”

The sculpture depicts a person walking across the backs of a school of fish painted in bright primary colors like an illustration from a children’s book. It’s based on a story told by the late Onondaga Nation Chief Irving Powless, Sr. about the abundance of fish once found in Onondaga Creek.

The sculpture depicts a person walking across the backs of a school of fish painted in bright primary colors like an illustration from a children’s book. It’s based on a story told by the late Onondaga Nation Chief Irving Powless, Sr. about the abundance of fish once found in Onondaga Creek.

Powless’s grandson, Brad Powless, first heard that story while fishing with his grandfather in the 1970s. He was among a small group of Onondaga Nation citizens who recently gathered on the bank of Onondaga Creek near Tully.

They’d come to talk about the unprecedented return in September of 1,000 acres of land to the Onondaga Nation, and along with it the headwaters of the creek that bears the name of their people.

“My grandfather was a woodsman and a fisherman, so I’m sure that he’s been here hunting and fishing,” Powless said, staring into the crystal-clear current that was somehow connected to the engineered, fenced-off, brown river winding through Syracuse 15 miles away.

“And it feels good to know that all our ancestors have been here fishing,” he said. “Feels very good.”

The gathering was a homecoming more than 200 years in the making that stirred deep feelings among the group’s five members.

“It’s really a very valuable spiritual thing for us to be able to come back here,” said Jeanne Shenandoah, the eldest in the group. “Now it’s up to us to determine whatever we want to see here.”

While their newly acquired land appeared to be a bucolic patchwork of rolling green fields and forests familiar to any Central New Yorker, problems lurked below the surface.

‘Our people have always been here’

‘Our people have always been here’

The land transfer is part of Honeywell International’s 2017 settlement with the U.S. and New York State for polluting Onondaga Lake and damaging its watershed.

It marks the end of more than a century of environmental degradation and neglect, and the first time land has been returned directly to any of the state’s eight federally recognized Native American tribes.

It’s also the largest land return by any state to an Indigenous nation and comes after four years of “intense discussions” with federal and state officials, said long-time Onondaga Nation attorney Joe Heath.

Unlike deals the U.S. has made with other Indigenous nations, the Onondagas refused to allow the land to be held in trust. They fought for “absolute jurisdiction of our homeland,” said Shenandoah.

But getting federal officials to direct Honeywell to hand over 1,000 acres with no strings attached was only the first hurdle. New York State had its own ideas about how the land should be managed.

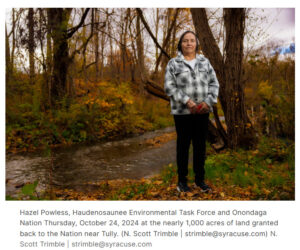

One of the big sticking points, said Hazel Powless, was the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s demand that the Nation install six parking lots to give trout anglers access to Onondaga Creek.

“And we’re like, no, we know how to take care of this land,” Powless said.