The Daily Orange

By Ahna Fleming

Onondaga Creek, muddied by more than 100 years of pollution, may soon flow with a renewed glimmer under the care of its original protectors, the Onondaga Nation.

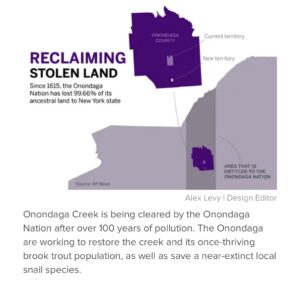

After reclaiming 1,000 acres of ancestral land on Sept. 30, the Onondaga are working to restore the creek and its once-thriving brook trout population, as well as save a local snail species on the brink of extinction.

The land is the largest plot ever returned to Indigenous peoples in the history of the United States. But the added 1,000 acres make up only 0.04% of the total 2.5 million of treaty-guaranteed land New York state has taken from the Onondaga since the 17th century.

“For the Onondaga people, there has always been that hurt about the loss of our lands,” Bradley Powless, a council member of the Onondaga Nation, said. “It does take one educating ourselves about how that happened, so we know to be mindful not to repeat those actions in the future. If you know how it happened, maybe you can help heal that hurt a little bit.”

‘A horrible, shameful history of colonialism’

Neal Powless, who is Bradley’s brother and serves as Syracuse University’s Ombuds, said discovering maps of the Onondaga’s territory in SU’s Bird Library — and seeing the Onondaga’s federally recognized land contrasted with the 2.5 million of which they are guaranteed sovereignty by treaty — shocked him.

“That was shock, that was frustration, little bit of anger,” he said. “To only have access to less than 1%, it’s still not enough to engage the way that we ancestrally know how to engage.”

1615 marked the first European colonial invasion of Onondaga territory. Before that, the Onondaga enjoyed the stewardship, protection and use of those 2.5 million acres, which runs roughly north and south through the center of New York, said Joe Heath, an SU alumnus and lawyer who represents the Onondaga.

The Nation is guaranteed sovereignty of that land under the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua and is currently pursuing a claim to get it back with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. If IACHR recommends that the land be returned to the Nation, it’s still not guaranteed to be enforced federally, The New York Times reported.

“Every foot of Turtle Island — and that’s how (Indigenous people) refer to North America — is Indian Country,” Heath said. “All of the land was taken illegally.”

French and English colonists justified the genocide of Native Americans and the theft of their land with the Doctrine of Discovery, a series of papal bulls — decrees ordered by the Pope — in the late 15th century.

The decrees gave Christian colonists the authority to invade and claim the resources of non-Christian lands, as well as subjugate and enslave non-Christian people, according to the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

“There’s no rational basis for it other than greed and money and racism and colonialism. It’s just a horrible, shameful history of colonialism,” Heath said. “Forced removal, which is ethnic cleansing — genocide. Boarding schools so that you can assimilate people, get them out of the way, make them ‘real Americans.’”

In 2023, the Vatican repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery, expelling it from the Catholic faith. When asked how such a doctrine found its way into U.S. federal law, Heath said “shamefully, is the only way to put it.”

The U.S. Supreme Court first cited the doctrine in its 1823 decision of Johnson v. McIntosh, ruling that Indigenous people could live on their land but not sell it. Heath said the doctrine was referenced “as if it were supreme law,” and the case has since become the basis for Federal Indian Law and land ownership in the U.S.

Most recently, the Supreme Court cited the Doctrine of Discovery in its 2005 ruling of City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York. The Oneida, a brother tribe of the Onondaga as part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, has territory about 25 miles east of SU’s campus.

The Oneida were denied the sovereignty of their ancestral land when the court held that repurchasing such land 200 years later doesn’t restore tribal sovereignty to that land, following the precedent set in Johnson v. McIntosh.

Federal law prohibited the Oneida “from rekindling embers of sovereignty that long ago grew cold,” the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in the opinion of the court, rejecting the return of land to the Oneida.

“The papal bull – if it’s current law, because that’s what it is, it’s current law – it means that I and my brother and any other Haudenosaunee or Indigenous person are equal to the dog and the rabbit and the squirrel outside,” Neal said. “We have no rights. We are a fauna. And that’s the justification — that in order for the USA to own land, I have to be equal to a rabbit.”

Neal said that the version of American history that’s frequently taught in schools nearly succeeded in erasing the Indigenous narrative by destroying papers or burning books, rendering it impossible to prove that which they know to be true. Seeing the maps in Bird Library of pre-colonial Onondaga territory confirmed to him that the Onondaga’s fight was justified.

“It doesn’t make sense, except if the courts and the law are all about justifying stealing their land, and that’s what U.S. Indian law is all about,” Heath said. “Colonialism is justified because the colonists write the history.”

Because an IACHR ruling doesn’t guarantee federal legal action, Heath said the Nation’s next step is to urge the Supreme Court to overturn the over-500-year-old doctrine.

“If you’re not sitting at the table, you’re on the table,” Neal said. “That’s the colonial perspective.”

Ginsburg wrote in the 2005 decision that the return of the Oneida’s land would “disrupt” central New York’s counties and towns, which she wrote have a “longstanding, distinctly non-Indian character.”

The Onondaga have maintained for over 40 years that they would not “push out any unwilling settler,” Heath said. The Nation wants to work together with the city and state to better protect the environment, he said.

“They know what it’s like to be forcibly removed. They will not repeat that on their neighbors,” he said.

Reclaiming the land is about more than just ownership or sovereignty, Neal said.

He compared the concept of land ownership to women’s status in marital relationships 100 years ago — “as property to do whatever they wanted to be done with them,” he said.

The perspective of marital relationships held by many people today allows both parties more autonomy, Neal said, which aligns more closely with the Onondaga’s view of the land.

“(It’s the) understanding that a good relationship is one that is a reciprocal relationship,” Neal said. “That’s how we see our relationship to the land.”

‘Clear, cold water’

With their reclaimed acreage, the Onondaga are committed to restoring the creek’s health.

Within the Nation’s 2.5 million treaty-guaranteed acres of territory, there are a multitude of rivers and streams. There used to be thousands of places to fish within the river system, and Onondaga Lake was abundant with brook trout, historically the main fish gathered by Onondaga fishermen.

Only five years ago, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recognized the Onondaga’s federal right to gather fish off of their territory and stopped issuing tickets to Onondaga citizens for fishing on their ancestral land, Heath said.

But by then, the creek had been polluted beyond return, flowing upstream to Onondaga Lake, which has been called the “most polluted lake in America.”

In 2012, the lake underwent a $1 billion cleanup project, funded by a federal Superfund settlement. At the time the project finished up, Onondaga Tadodaho Sid Hill called it an “expensive Band-Aid.”

For nearly 150 years, Honeywell International Incorporated polluted the lake and creek with chemicals such as mercury, and degraded the environment with its salt mining, Heath said.

The pollution led to a phenomenon called mudboils, mixtures of muddy salt water, silt and clay that dump nearly 20 tons of silt and sand into Onondaga Creek every day. The mudboils made the creek uninhabitable for brook trout, Heath said.

Now that they have a small portion of their land back, the Nation is working to restore the brook trout population. The fish, native to the creek, are highly sensitive to temperature and clarity, so it’s important to have “clear, cold water,” Heath said.