Central Current

by Patrick McCarthy

Sid Hill eased his pickup truck through a yawning gate and into a snow-hampered pasture.

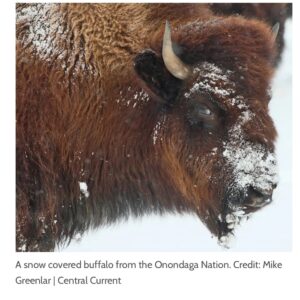

Nearly 70 buffalo cast expectant, snow-tinged glances up at the approaching vehicle.

Hill, the Tadodaho of the Onondaga Nation, had not come to feed the bison, but rather to watch the feeding. As the hungry bison circled Hill’s pickup, their feed began lumbering up the hill behind them. Mitch Laffin drove a tractor front-loaded with a massive hay bale into the pasture.

Hill remembers feeding the buffalo decades ago, when the herd numbered around 20.

“I never thought it would get this big,” Hill said.

The Onondaga bison herd grew out of an agreement now 50 years old. Neighboring rancher Brad Tiffany raised a small herd on his Lafayette farm and gifted some to the Nation in 1975. Like the Onondaga themselves, the bison — which the Onondaga call dege·yá’gih — withstood the American government’s genocidal campaigns.

It was, in part, Tiffany who helped them bring buffalo back to the region. Tiffany gifted them 11 buffalo and the Onondaga gave him sassafras. They commemorated the agreement with a treaty depicting their terms.

Most Central New Yorkers have never heard of this agreement. This spring, they’ll have the opportunity to view the treaty at the Ska-Nonh Great Law Of Peace Center. The Haudenosaunee cultural education museum sits on the north shore of Onondaga Lake.

There in the pasture, Hill thought back to his own time feeding the bison 40 years ago. He smiled while recounting an old story of the herd breaking out of the pasture. He reflected on the woodland bison that once roamed the Tully Valley.

This herd needs care and a steady supply of hay, Hill said, but the bison don’t need much else.

“They’re pretty durable.”

A gory history

Reintroducing American buffalo, or bison, to Central New York was Brad Tiffany’s dream.

Tiffany’s family owned the local Scotch and Sirloin steakhouse franchise, and Brad owned a 250-acre ranch in Lafayette. His son, Lars, said that Brad’s goal to steward American buffalo had its roots in middle school, when Brad learned about the 19th-century near-annihilation of American buffalo.

As the nation chased its “Manifest Destiny” to the gold-laden coasts of California, that western progress carved a bloody path across the Heartland.

In a post-World War II era imbued with patriotism, Brad struggled to reckon his national pride with the brutal, blood-soaked bison history he had learned. Americans drove the continent’s wild buffalo population, which once numbered 30 to 60 million, to near extinction. The National Park Service estimates that by the 1890’s, fewer than 1,000 bison remained.

“To him, it was a huge black eye on this incredible country and nation,” Lars said.

During the “Great Slaughter,” the American government, military, and civilians intertwined the elimination of the American buffalo and Indigenous people. The campaign is often referred to as as the “buffalo genocide.”

Buffalo were killed for their hides and tongues, but also to reduce their numbers. Herds were seen as a nuisance to railroad construction and operation. Others killed bison for sport.

Construction of the Transcontinental Railroad severed the Great Plains buffalo into two separate populations, making them more susceptible to hunting.

Theodore Roosevelt, the “conservationist president,” justified the buffalo slaughter as the regrettable means to a necessary end: the erasure and subjugation of Indigenous peoples.

While lamenting the near-annihilation of the American buffalo in 1904, then-president Roosevelt wrote, “Above all, the extermination of the buffalo was the only way of solving the Indian question.”

Estimates vary, but historical consensus approximates that in 1700, at least 5 million indigenous people lived in what is now the contiguous U.S.

By 1900, the American government’s century-long conquest reduced the population of these Indigenous people to less than 240,000 – and the population of buffalo to less than 1,000.

“From the standpoint of humanity at large,” Roosevelt wrote in 1904, “the extermination of the buffalo has been a blessing.”